The post-COVID years haven’t been type to skilled forecasters, whether or not from the non-public sector or coverage establishments: their forecast errors for each output development and inflation have elevated dramatically relative to pre-COVID (see Determine 1 in this paper). On this two-post sequence we ask: First, are forecasters conscious of their very own fallibility? That’s, once they present measures of the uncertainty round their forecasts, are such measures on common according to the dimensions of the prediction errors they make? Second, can forecasters predict unsure instances? That’s, does their very own evaluation of uncertainty change on par with modifications of their forecasting capability? As we’ll see, the reply to each questions sheds gentle of whether or not forecasters are rational. And the reply to each questions is “no” for horizons longer than one 12 months however is probably surprisingly “sure” for shorter-run forecasts.

What Are Probabilistic Surveys?

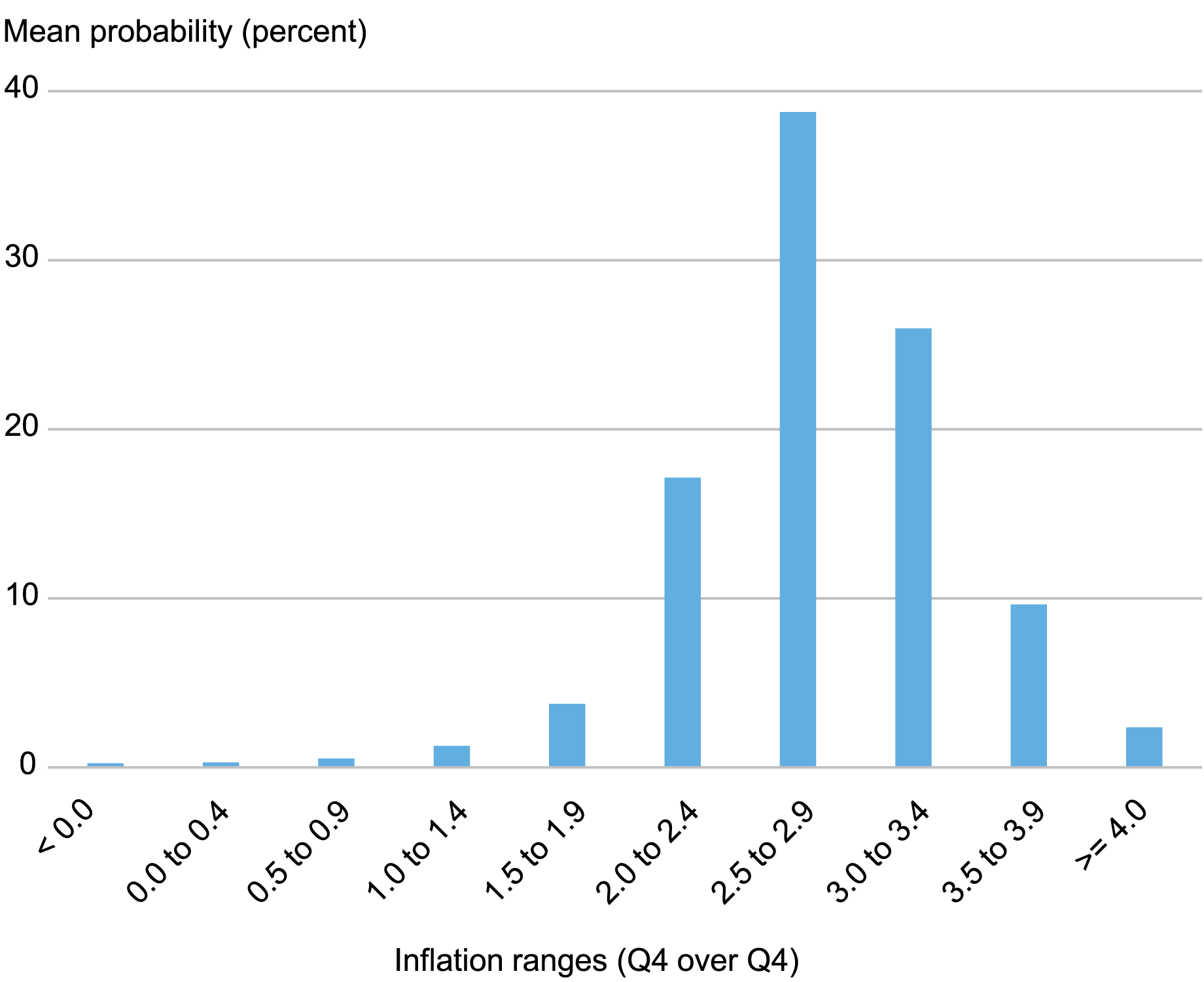

Let’s begin by discussing the information. The Survey of Skilled Forecasters (SPF), carried out by the Federal Reserve Financial institution of Philadelphia, elicits each quarter projections from a variety of people who, in accordance with the SPF, “produce projections in achievement of their skilled obligations [and] have lengthy observe information within the area of macroeconomic forecasting.’’ These persons are requested for level projections for a variety of macro variables and in addition for chance distributions for a subset of those variables similar to actual output development and inflation. The way in which the Philadelphia Fed asks for chance distributions is by dividing the actual line (the interval between minus infinity and plus infinity) into “bins” or “ranges”—say, lower than 0, 0 to 1, 1 to 2, …—and asking forecasters to place possibilities to every bin (see right here for a current instance of the survey type). The end result, when averaged throughout forecasters, is the histogram proven beneath for the case of core private consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation projections for 2024 (additionally proven on the SPF web site).

An Instance of Solutions to Probabilistic Surveys

Word: The chart plots imply possibilities for core PCE inflation in 2024.

So, as an example, in mid-Might, forecasters anticipated on common a 40 % chance that core PCE inflation in 2024 will probably be between 2.5 and 2.9 %. Probabilistic surveys, whose examine was pioneered by the economist Charles Manski, have an a variety of benefits in comparison with surveys that solely ask for level projections: they supply a wealth of knowledge that’s not included in level projections, for instance, on uncertainty and dangers to the outlook. Because of this, probabilistic surveys have change into an increasing number of in style in recent times. The New York Fed’s Survey of Shopper Expectations (SCE), for instance, is a shining instance of a very talked-about probabilistic survey.

With a purpose to acquire from probabilistic surveys data that’s helpful to macroeconomists—for instance, measures of uncertainty—one has to extract the chance distribution underlying the histogram and use it to compute the thing of curiosity; if one is excited about uncertainty, that may be the variance or an interquartile vary. The way in which that is normally performed (as an example, within the SCE) is to imagine a particular parametric distribution (within the SCE case, a beta distribution) and to decide on its parameters in order that it most closely fits the histogram. In a current paper with my coauthors Federico Bassetti and Roberto Casarin, we suggest another strategy, primarily based on Bayesian nonparametric methods, that’s arguably extra strong because it relies upon much less on the particular distributional assumption. We argue that for sure questions, similar to whether or not forecasters are overconfident, this strategy makes a distinction.

The Evolution of Subjective Uncertainty for SPF Forecasters

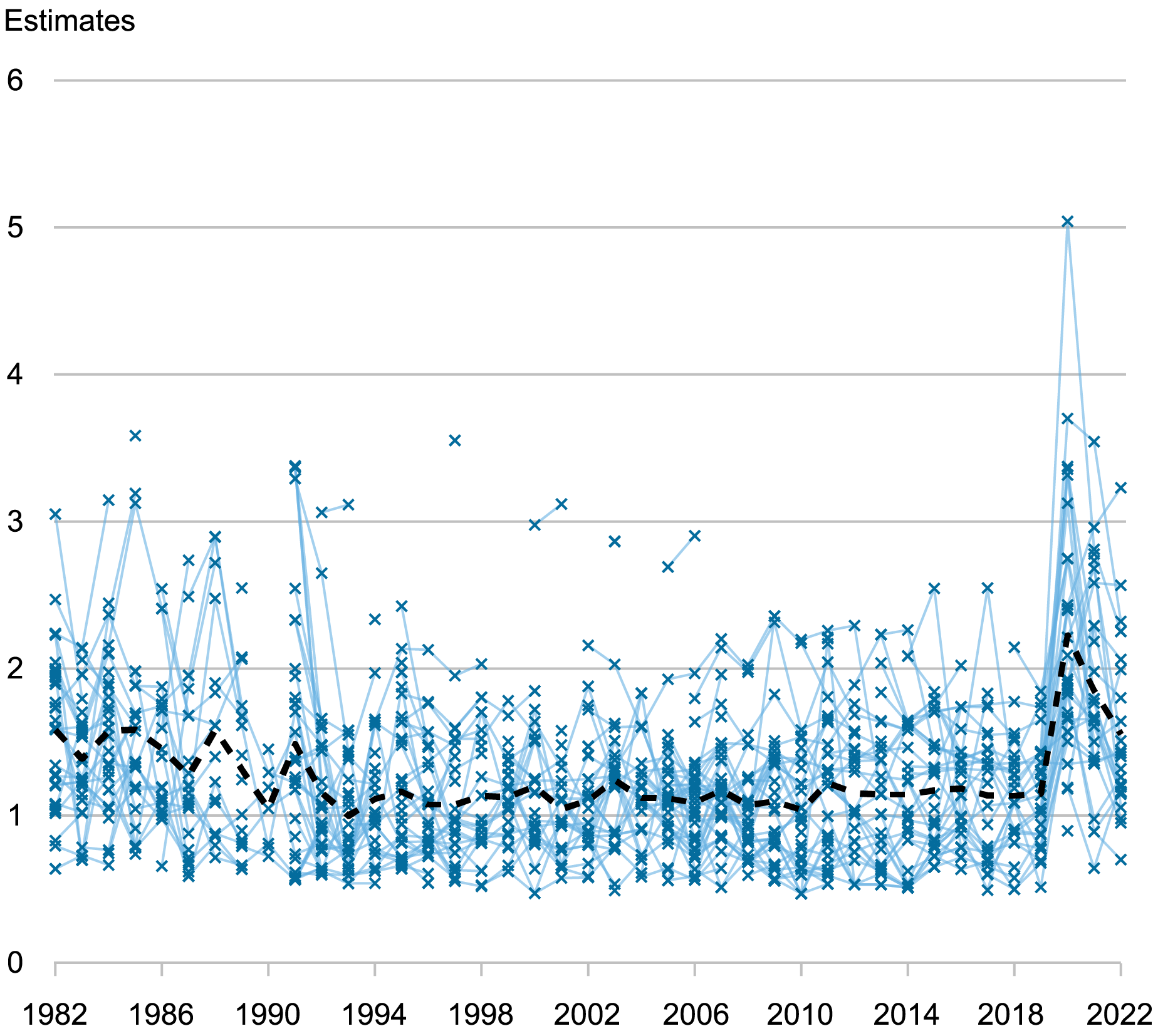

We apply our strategy to particular person probabilistic surveys for actual output development and GDP deflator inflation from 1982 to 2022. For every respondent and every survey, we then assemble a measure of subjective uncertainty for each variables. The chart beneath plots these measures for subsequent 12 months’s output development (that’s, in 1982 this might be the uncertainty about output development in 1983). Particularly, the skinny blue crosses point out the posterior imply of the usual deviation of the person predictive distribution. (We use the usual deviation versus the variance as a result of its items are simply grasped quantitatively and are comparable with different measures of uncertainty such because the interquartile vary, which we embody within the paper’s appendix. Recall that the items of a normal deviation are the identical as these of the variable being forecasted.) Skinny blue strains join the crosses throughout intervals when the respondent is identical. This manner you’ll be able to see whether or not respondents change their view on uncertainty. Lastly, the thick black dashed line reveals the common uncertainty throughout forecasters in any given survey. On this chart we plot the end result for the survey collected within the second quarter of every 12 months, however the outcomes for various quarters are very related.

Subjective Uncertainty for Subsequent 12 months’s Output Development by Particular person Respondent

Notes: Uncertainty (indicated by skinny blue crosses) is measured by the posterior imply of the usual deviation of the predictive distribution for every respondent. The thick black dashed line reveals the common uncertainty throughout forecasters in any given survey.

The chart reveals that, on common, uncertainty for output development projections declined from the Eighties to the early Nineties, seemingly reflecting a gradual studying concerning the Nice Moderation (a interval characterised by much less volatility in enterprise cycles), after which remained pretty fixed as much as the Nice Recession, after which it ticked up towards a barely larger plateau. Lastly, in 2020, when the COVID pandemic struck, common uncertainty grew twofold. The chart additionally reveals that variations in subjective uncertainty throughout people are very massive and quantitatively trump any time variation in common uncertainty. The usual deviation of low-uncertainty people stays beneath one all through a lot of the pattern, whereas that of high-uncertainty people is commonly larger than two. The skinny blue strains additionally present that whereas subjective uncertainty is persistent—low-uncertainty respondents have a tendency to stay so—forecasters do change their minds over time about their very own uncertainty.

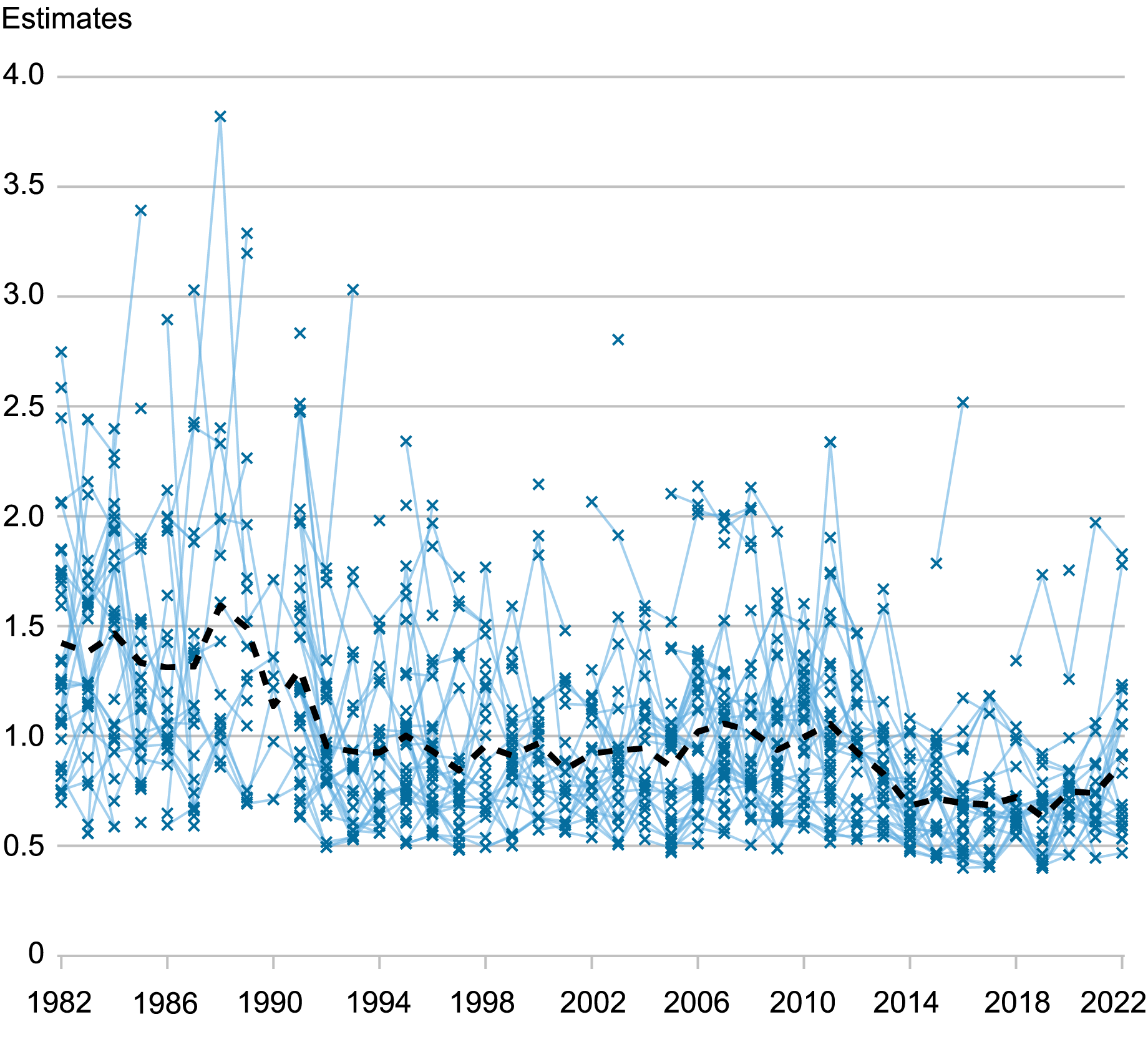

The following chart reveals that, on common, subjective uncertainty for subsequent 12 months’s inflation declined from the Eighties to the mid-Nineties after which was roughly flat up till the mid-2000s. Common uncertainty rose within the years surrounding the Nice Recession, however then declined once more fairly steadily beginning in 2011, reaching a decrease plateau round 2015. Apparently, common uncertainty didn’t rise dramatically in 2020 by way of 2022 regardless of COVID and its aftermath, and even supposing, for many respondents, imply inflation forecasts (and the purpose predictions) rose sharply.

Subjective Uncertainty for Subsequent 12 months’s Inflation by Particular person Respondent

Notes: Uncertainty (indicated by the skinny blue crosses) is measured by the posterior imply of the usual deviation of the predictive distribution for every respondent. The thick black dashed line reveals the common uncertainty throughout forecasters in any given survey.

Are Skilled Forecasters Overconfident?

Clearly, the heterogeneity in uncertainty simply documented flies within the face of full data rational expectations (RE): if all forecasters used the “true” mannequin of the economic system to provide their forecasts—no matter that’s—they might all have the identical uncertainty and that is clearly not the case. There’s a model of RE, referred to as noisy RE, that will nonetheless be in step with the proof: in accordance with this concept, forecasters obtain each private and non-private alerts concerning the state of the economic system, which they don’t observe. Heterogeneity within the alerts, and of their precision, explains the heterogeneity of their subjective uncertainty: forecasters receiving a poor/extra exact sign have larger/decrease subjective uncertainty. Nonetheless, beneath RE, their subjective uncertainty higher match the standard of their forecasts as measured by their forecast error—that’s, forecasters must be neither over- nor under-confident. We check this speculation by checking whether or not, on common, the ratio of ex-post (squared) forecast errors over subjective uncertainty, as measured by the variance of the predictive distribution, equals one.

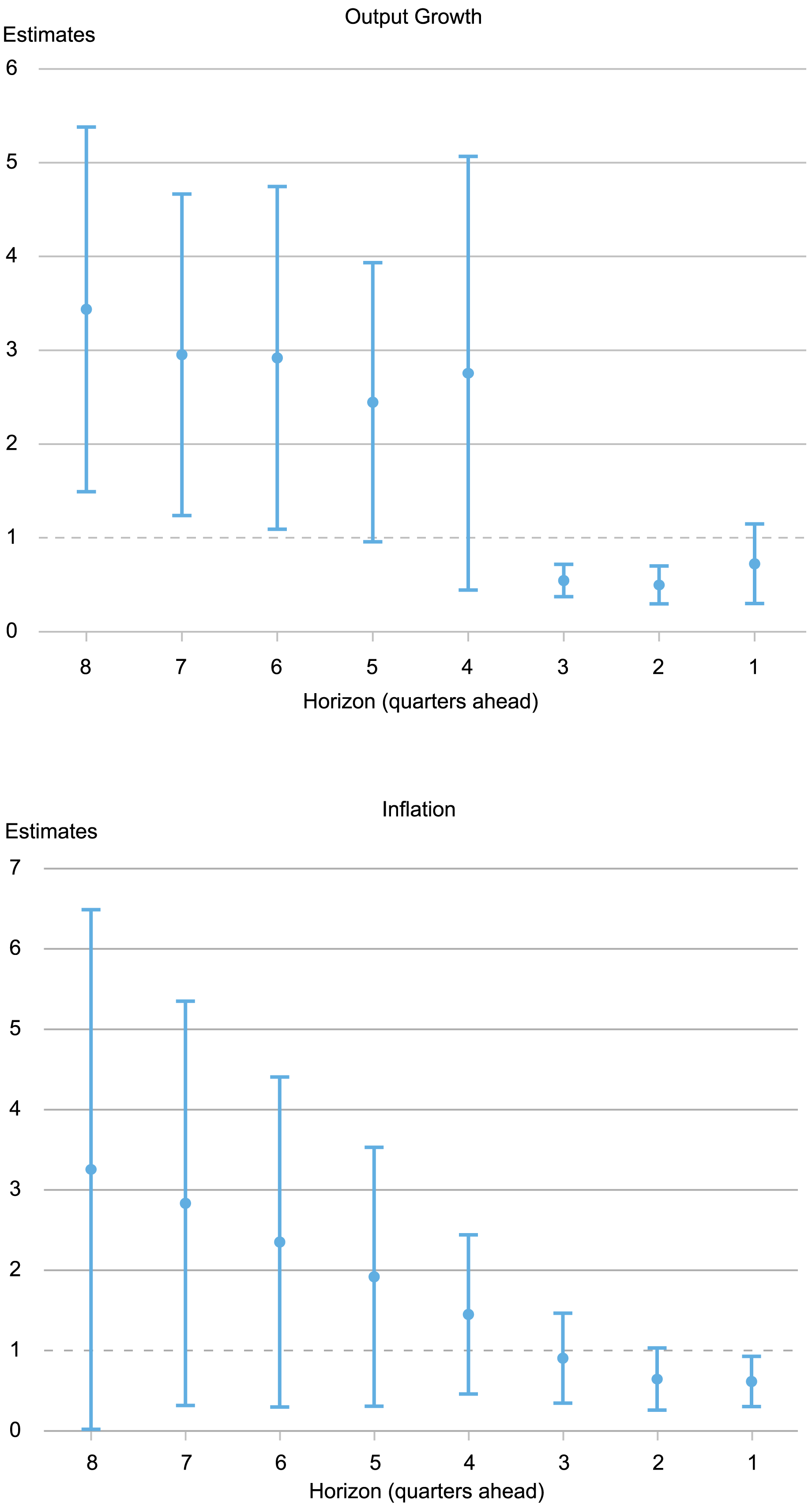

The thick dots in charts beneath present the common ratio of squared forecast errors over subjective uncertainty for eight to at least one quarters forward (the eight-quarter-ahead measure makes use of the surveys carried out within the first quarter of the 12 months earlier than the conclusion; the one-quarter-ahead measure makes use of the surveys carried out within the fourth quarter of the identical 12 months), whereas the whiskers point out 90 % posterior protection intervals primarily based on Driscoll-Kraay normal errors.

Do Forecasters Over- or Beneath- Estimate Uncertainty?

Notes: The dots present the common ratio of squared forecast errors over subjective uncertainty for eight to at least one quarters-ahead. The whiskers point out 90 % posterior protection intervals primarily based on Driscoll-Kraay normal errors.

We discover that for lengthy horizons—between two and one years—forecasters are overconfident by an element starting from two to 4 for each output development and inflation. However the reverse is true for brief horizons: on common forecasters overestimate uncertainty, with level estimates decrease than one for horizons lower than 4 quarters (recall that one signifies that ex-post and ex-ante uncertainty are equal, as must be the case beneath RE). The usual errors are massive, particularly for lengthy horizons. For output development, the estimates are considerably above one for horizons larger than six, however, for inflation, the 90 % protection intervals all the time embody one. We present within the paper that this sample of overconfidence at lengthy horizons and underconfidence at quick horizons is powerful throughout completely different sub-samples (e.g., excluding the COVID interval), though the diploma of overconfidence for lengthy horizons modifications with the pattern, particularly for inflation. We additionally present that it makes an enormous distinction whether or not one makes use of measures of uncertainty from our strategy or that obtained from becoming a beta distribution, particularly at lengthy horizons.

Whereas the findings are according to the literature on overconfidence (see the quantity edited by Malmendier and Taylor [2015]) for output for horizons larger than one 12 months, outcomes are extra unsure for inflation. For horizons shorter than three quarters, the proof reveals that forecasters if something overestimate uncertainty for each variables. What would possibly clarify these outcomes? Patton and Timmermann (2010) present that dispersion in level forecasts will increase with the horizon and argue that this result’s in step with variations not simply in data units, because the noisy RE speculation assumes, but additionally in priors/fashions, and the place these priors matter extra for longer horizons. In sum, for brief horizons forecasters are literally barely higher at forecasting than they assume they’re. For lengthy horizons, they’re lots worse at forecasting and they aren’t conscious of it.

In immediately’s put up we regarded on the common relationship between subjective uncertainty and forecast errors. Within the subsequent put up we’ll take a look at whether or not variations in uncertainty throughout forecasters and/or over time map into variations in forecasting accuracy. We’ll see that once more the forecast horizon issues lots for the outcomes.

Marco Del Negro is an financial analysis advisor in Macroeconomic and Financial Research within the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York’s Analysis and Statistics Group.

Tips on how to cite this put up:

Marco Del Negro , “Are Skilled Forecasters Overconfident? ,” Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York Liberty Avenue Economics, September 3, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/09/are-professional-forecasters-overconfident/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed on this put up are these of the creator(s) and don’t essentially mirror the place of the Federal Reserve Financial institution of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the duty of the creator(s).